Composition

"Caravaggio meets Harry Lime"

I would like to share with you some thoughts on the art of composition - in fine art, on stage and in film

French, 14th Century

Composition in representational art involves a complex combination of form and color that invariably reconstructs some kind of recognizable 'reality'

In the medieval painting above, for example, there is some attempt at perspective but it is inconsistent. Note the disparity between the fore-ground figures on the left and the right of frame. Those on the right are larger principally because their importance (status) is greater.

The representation of three-dimensional images on a flat canvas needed the mathematical innovations and disciplines of the painters and architects of the Renaissance to achieve any kind of visual credibility

The Delivery of the Keys (1481/82) Sistine Chapel, Rome

Artists like Filippo Brunelleschi (1337-1446) and Pietro Perugino (1450-1523) were amongst the first to apply a mathematical basis to representing architectural space on a flat canvas

So, what therefore are the basic rules of perspective?

Orthogonal

Let's start with spacial depth - the process in art in which we represent vanishing perspective

From Perspective - Jan Vredeman de Vries (1604)The rules of perspective as defined by the architects and painters of the period are very rigid. Everything within the frame (in this case, furniture as well as arches) must conform to clearly defined 'rules'

What art uses in this process is a receding grid of lines (orthogonals) that converge at given point (known as the vanishing point) on a chosen horizon

From Perspective - Jan Vredeman de Vries (1604)

This enabled artists to compose their pictures within a mathematical format. This did not necessarily make for great paintings but at least it was now possible to represent depth of field consistently

This format survived for hundreds of years - until Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque subverted Renaissance 'rules' by introducing more than one vanishing point, thereby creating competing planes within one picture

Le Gueridon (1929) - Georges Braque

In this painting, Georges Braque (1882-1963) has hinted at 'normal' perspective in the angled panels of the room but has subverted these conventional rules by deliberately tilting the plane of the table vertically, towards the viewer

Representational art would never be the same again!

The beheading of St. John the Baptist -Caravaggio

In the above painting by Caravaggio (1571-1610) - an early exponent of experimental lighting in art - the figures occupy the same plane and are lit by a single source of light (from frame left, as you face it).

Some sense of depth is provided by the figure at the window. This form of dynamic composition was new in art at this period, especially when combined with 'dramatic' lighting to accentuate form

In representational art, the challenge is to represent depth within the two-dimensional frame of the canvas

Not always easy!

The Calling of St. Matthew - Caravaggio

Here Caravaggio has opted for strong 'natural' light from a window - a 'realistic' device but used in a very sophisticated way. The directional light not only separates the seated characters one from the other but gives the composition both coherence and drama

Lighting here is also used as some kind of inspiration or revelation - a device employed in other works by this artist

Caravaggio - Supper of Emmaus

Here Caravaggio has composed his three principal figures into a triangle, the shape of which is articulated by the raised right hand of the central figure and the extended arms of the old man on right of frame

Caravaggio - Detail from Supper of Emmaus

This detail of the standing figure shows the subtle effect of the directional light coming from top left of frame as we face the painting. It gives it an almost photographic reality

The Sacrifice of Issac - Caravaggio

Here a strong shaft of directional light coming from top left of frame as you face the painting accentuates the powerful diagonal shape of the composition - both drawing attention from the outstretched arm of the figure on the left, to the knife and thence on down to the boy's terrified face

David - Caravaggio

This highly developed use of chiaroscuro (light and shade to define form) is what marks Carvaggio's work out from his contemporaries.

Perspective in the Theater

This enabled artists to compose their pictures within a mathematical format. This did not necessarily make for great paintings but at least it was now possible to represent depth of field consistently

This format survived for hundreds of years - until Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque subverted Renaissance 'rules' by introducing more than one vanishing point, thereby creating competing planes within one picture

Le Gueridon (1929) - Georges Braque

In this painting, Georges Braque (1882-1963) has hinted at 'normal' perspective in the angled panels of the room but has subverted these conventional rules by deliberately tilting the plane of the table vertically, towards the viewer

Representational art would never be the same again!

However, pictorial form (buildings, figures etc.) is not simply a matter of realistic composition but of

lighting - darkness and shade - and the relative position of figures

within that frame

The beheading of St. John the Baptist -Caravaggio

In the above painting by Caravaggio (1571-1610) - an early exponent of experimental lighting in art - the figures occupy the same plane and are lit by a single source of light (from frame left, as you face it).

Some sense of depth is provided by the figure at the window. This form of dynamic composition was new in art at this period, especially when combined with 'dramatic' lighting to accentuate form

Fore-ground/background disposition of figures

In representational art, the challenge is to represent depth within the two-dimensional frame of the canvas

Not always easy!

The Calling of St. Matthew - Caravaggio

Here Caravaggio has opted for strong 'natural' light from a window - a 'realistic' device but used in a very sophisticated way. The directional light not only separates the seated characters one from the other but gives the composition both coherence and drama

Lighting here is also used as some kind of inspiration or revelation - a device employed in other works by this artist

Caravaggio - Supper of Emmaus

Here Caravaggio has composed his three principal figures into a triangle, the shape of which is articulated by the raised right hand of the central figure and the extended arms of the old man on right of frame

Caravaggio - Detail from Supper of Emmaus

This detail of the standing figure shows the subtle effect of the directional light coming from top left of frame as we face the painting. It gives it an almost photographic reality

The Sacrifice of Issac - Caravaggio

Here a strong shaft of directional light coming from top left of frame as you face the painting accentuates the powerful diagonal shape of the composition - both drawing attention from the outstretched arm of the figure on the left, to the knife and thence on down to the boy's terrified face

David - Caravaggio

This highly developed use of chiaroscuro (light and shade to define form) is what marks Carvaggio's work out from his contemporaries.

Since, by definition, theatrical space is three-dimensional, the rules of perspective apply equally to this particular art form

Giselle - Birmingham Royal Ballet, designed by Mark Jonathan (1999)

This magnificent stage-set within a ruined chapel contains all the same elements one might find in a late Renaissance painting

Indeed, it is likely that the flat representing the end wall of the chapel is deliberately smaller - to accentuate the effect of a vanishing perspective.

Someone is going to come - Opera Vest, Bergen

Designer - Simon Banham

This simple stage-set accentuates stage depth by using very basic orthognal construction - but look how lighting can transform the same set dramatically

The disposition of (moving) actors in space and their intimate relation to both setting and lighting shapes the aesthetic of stage productions - as, indeed, it does in representational art

Wozzeck - Alban Berg, Santa Fe Opera (2001)

Designer - Rick Fisher

Here the actor dominates the foreground but dramatic side lighting of the extensive area behind him makes his isolation even for effective

Under Milk Wood - Dylan Thomas, Theatr Clwyd, Mold (2001)

Designer Martyn Bainbridge

This beautiful set for Under Milk Wood is highly functional and yet manages to capture the magic of Thomas' eccentric Welsh village.

Theater and my painting

I began my professional career in the theater as a stage director. I also developed an interest at that time in stage-design

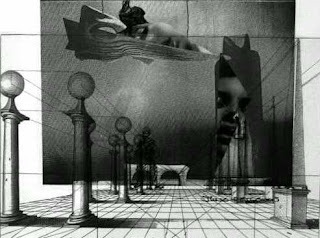

The Tempest by William Shakespeare, Oxford Playhouse

Preliminary design by Mike Healey

Preliminary design for a backcloth for Midsummer Night's Dream by Mike Healey

That means my work as an artist now is partly shaped by those early experiences and disciplines

Caliban's Garden - Mike Healey (2009)

Above is a boxed, three-dimensional 'stage set' in which I have incorporated 17th Century architectural components, after Jan Vredeman de Vries (1604/5)

The box containing this set is about 20 centimeters deep

Alice in Wonderland Revisited - Mike Healey (2003)

I have used this technique in two-dimensional work to give spatial depth and 'drama' to my paintings and graphic work

Above is a boxed, three-dimensional 'stage set' in which I have incorporated 17th Century architectural components, after Jan Vredeman de Vries (1604/5)

The box containing this set is about 20 centimeters deep

Alice in Wonderland Revisited - Mike Healey (2003)

I have used this technique in two-dimensional work to give spatial depth and 'drama' to my paintings and graphic work

Skeletal Forest - Mike Healey

In this small landscape I have allowed a small architectural element to creep in (frame right) in order to heighten the denuded forest scene - skeletal scaffolding within a skeletal forest

Composition in Film

Much of what I have explored above applies equally to film, whether shot on location or in the studio

This is the first time we meet Harry Lime (Orson Welles) - perhaps one of the best 'entrances' in the history of cinema!

Let's start by looking at a classic film - The Third Man

(1949) - directed by Carol Reed, written by Graham Greene and starring

Joseph Cotten, Alida Valli, Trevor Howard and Orson Welles

Alida Valli

The Third Man is set in Vienna immediately after the war. Orson Welles plays Harry Lime, a murderous black-marketeer whose mysterious 'death' is investigated by both his friend Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) and the international police

I have chosen this film partly because it is probably well known to most of you but also because, being black and white, its compositional characteristics and lighting are more evident

Dark, moody, dangerous - the real war-damaged Vienna is shot by lighting-cameraman Robert Krasker with exceptional flair, using German Expressionism to enrich his own version of Film Noir

Krasker was Lighting Cameraman on Brief Encounter (1945) for David Lean - another British film classic

It is worth remembering that Citizen Kane, directed by Orson Welles, was released only four years earlier. Its impact on film makers like Carol Reed was enormous.

You should be familiar with this composition by now - is it so far removed from the architectural conceits of Renaissance art or the moody, dramatic settings for Caravaggio's murders and martydoms?

In film, in which real or built sets are naturally three-dimensional, the trick is to enhance that characteristic with subtle lighting

As in Caravaggio's work, chiaroscuro is similarly used here for dramatic effect. In this scene the primary source of light is from the street but in order to highlight the woman's face, a second source of light is added from camera left

Note also the way the cameraman has tilted his camera slightly. The effect is unsettling, and deliberately so.

Carol Reed was criticized for this when the film was released

Alida Valli

The Third Man is set in Vienna immediately after the war. Orson Welles plays Harry Lime, a murderous black-marketeer whose mysterious 'death' is investigated by both his friend Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) and the international police

I have chosen this film partly because it is probably well known to most of you but also because, being black and white, its compositional characteristics and lighting are more evident

Dark, moody, dangerous - the real war-damaged Vienna is shot by lighting-cameraman Robert Krasker with exceptional flair, using German Expressionism to enrich his own version of Film Noir

Krasker was Lighting Cameraman on Brief Encounter (1945) for David Lean - another British film classic

It is worth remembering that Citizen Kane, directed by Orson Welles, was released only four years earlier. Its impact on film makers like Carol Reed was enormous.

You should be familiar with this composition by now - is it so far removed from the architectural conceits of Renaissance art or the moody, dramatic settings for Caravaggio's murders and martydoms?

In film, in which real or built sets are naturally three-dimensional, the trick is to enhance that characteristic with subtle lighting

As in Caravaggio's work, chiaroscuro is similarly used here for dramatic effect. In this scene the primary source of light is from the street but in order to highlight the woman's face, a second source of light is added from camera left

Note also the way the cameraman has tilted his camera slightly. The effect is unsettling, and deliberately so.

Carol Reed was criticized for this when the film was released

Joseph Cotten in The Third Man

This simple but very effective composition requires multiple lighting from different sources to achieve the desired effect. I reckon there are at least five lamps in use. What do you think?

In Vienna after the war there was a very limited electricity supply so this is a highly contrived, cinematic effect that one would not experience in that reality

This simple but very effective composition requires multiple lighting from different sources to achieve the desired effect. I reckon there are at least five lamps in use. What do you think?

In Vienna after the war there was a very limited electricity supply so this is a highly contrived, cinematic effect that one would not experience in that reality

Joseph Cotten and Trevor Howard

This is a typical scene from The Third Man. The fore-gound figures are primarily lit from camera right with some fill on Trevor Howard's face from camera left.

Note, though, how depth is given to the frame by subtle lighting (from camera left only) of the architectural space behind the actors. The strongest light is reserved for the passage way at the far back - effectively giving the scene great depth of field

The Third Man - starring Joseph Cotten

In this beautiful, moody shot Cotten's face is lit subtly from camera right only

Strong back light (floods) placed far behind the train creates depth and smoky atmosphere of this Viennese railway station.

Here Carol Reed (Director) uses back light to shape his shot, tilting the camera to camera right to give it a disturbing element. The strong diagonal composition makes this a classic Film Noir frame.

In this variation of the previous composition, the director has added the shadow of Harry Lime running away from camera

Again note the pronounced diagonal composition with a single light source, top camera right. The shadow was probably created by a different light source onto an unseen figure bottom left or perhaps even added optically later

Harry Lime - on the run

In the celebrated chase scene in the sewers of Vienna, every lighting trick is used - with dramatic effect.

This must be one of the most exciting sequence in cinema - edited with extraordinary panache by Oswald Hafenrichter

This is a typical scene from The Third Man. The fore-gound figures are primarily lit from camera right with some fill on Trevor Howard's face from camera left.

Note, though, how depth is given to the frame by subtle lighting (from camera left only) of the architectural space behind the actors. The strongest light is reserved for the passage way at the far back - effectively giving the scene great depth of field

The Third Man - starring Joseph Cotten

In this beautiful, moody shot Cotten's face is lit subtly from camera right only

Strong back light (floods) placed far behind the train creates depth and smoky atmosphere of this Viennese railway station.

Here Carol Reed (Director) uses back light to shape his shot, tilting the camera to camera right to give it a disturbing element. The strong diagonal composition makes this a classic Film Noir frame.

In this variation of the previous composition, the director has added the shadow of Harry Lime running away from camera

Again note the pronounced diagonal composition with a single light source, top camera right. The shadow was probably created by a different light source onto an unseen figure bottom left or perhaps even added optically later

Harry Lime - on the run

In the celebrated chase scene in the sewers of Vienna, every lighting trick is used - with dramatic effect.

This must be one of the most exciting sequence in cinema - edited with extraordinary panache by Oswald Hafenrichter

I hope this exploration of some of the more basic elements of composition across three media has been of interest

It is a vast subject and I know that I cannot do it justice in

a short article like this!

Mike Healey

It is a vast subject and I know that I cannot do it justice in

a short article like this!

Mike Healey

The stage illustrations are taken from 2D/3D - Design for Theatre and Performance - catalogue from exhibition at Millennium Galleries, Sheffield (2002)

and

Time and Space, catalogue published by The British Society of Theater Designers (1999)

If you want better reproductions of Caravaggio's paintings than I can manage on my camera, start with the following link:

Caravaggio - The Complete Works

The Third Man is available on DVD from Studio Canal

If you also love the zither music of Anton Karas, its available at

ANTON KARAS

and

Time and Space, catalogue published by The British Society of Theater Designers (1999)

If you want better reproductions of Caravaggio's paintings than I can manage on my camera, start with the following link:

Caravaggio - The Complete Works

The Third Man is available on DVD from Studio Canal

If you also love the zither music of Anton Karas, its available at

ANTON KARAS

No comments:

Post a Comment